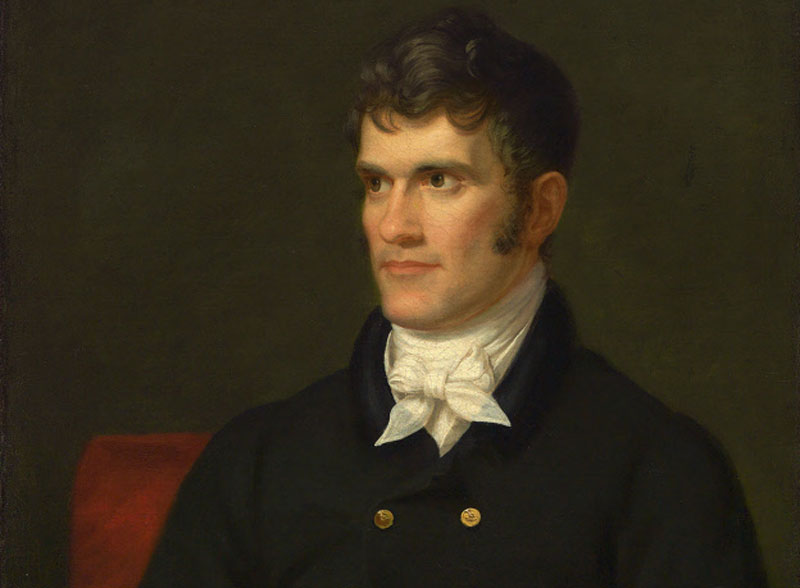

Remembering John C. Calhoun

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson through Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, arranged for an elaborate Democratic Party dinner to celebrate on April 13, the birthday of Thomas Jefferson and the Jeffersonian principles of the new Democratic Party. This was held at Brown’s Indian Queen Hotel in Washington. Political tension was increasing because of the effects of the substantial and controversial tariff increases that had been passed in 1828. These tariffs favored Northern manufacturers and punished farmers, especially those exporting agricultural products. The tariffs were having the most devastating economic impact on the cotton producing states of the South. Among these, South Carolina, was suffering the most.

Jackson’s Vice President, John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, one of the guests of honor, had become one of the leading spokesmen against the “Tariff of Abomination.” He, along with many Southern leaders, believed that the tariff of 1828 was unconstitutional because it subsidized one branch of industry, manufacturing, at the expense of commerce and agriculture. Calhoun maintained that a tariff should not tax one section of the economy or one region of the country for the benefit of another. He also believed that a tax on all the people should not be levied for the exclusive enrichment of only a part of the people. There was talk in the South Carolina legislature of Nullification, refusing to comply with such an unconstitutional, unfair, and very damaging law. There was even talk of Secession.

Senator Robert Hayne of South Carolina was to be the speaker that evening. After his remarks would come both voluntary and special toasts. Besides unifying the Party, Jackson looked upon the toasts as an opportunity for him to promote national and Democratic Party unity and to indicate his displeasure with any talk of Nullification.

Senator Hayne spoke, denouncing the tariff but avoiding any mention of Nullification. But when the voluntary toasts began, they took on an increasingly anti-tariff tenor, and the Pennsylvania delegation walked out.

When it came time for the special toasts, the tension was high. President Jackson rose, holding his glass before him. Rather than sweeping his eyes across the audience, he stared sternly at Calhoun alone and said,

“Our Union, it must be preserved.”

The Vice President was next to give his toast. The room was deadly quiet and the tension building even higher. Slowly Calhoun stood, lifted his glass, and in a firm voice directly addressed the President:

“The Union, next to our liberty, most dear.”

He paused for a moment and then to make his point unmistakably clear continued,

“May we all remember that it can only be preserved by respecting the rights of the states and by distributing equally the benefits and burdens of the Union.”

We may draw a lesson from this famous drama. Union or unity is a beneficial condition of like minded men, but it is not a condition so beneficial that it outweighs every other condition, principle, or virtue. Unity by no means outweighs in their various degrees considerations of liberty, truth, honor, justice, high moral principle, or spiritual fidelity. It cannot outweigh essential human dignities and unalienable rights. If unity does not serve mutual benefit, virtue and principle, its value is nullified. Furthermore, real unity cannot be coerced. Union forced at the point of a bayonet is tyranny and the enemy of liberty and all its virtues and blessings.

Tensions, however, grew worse in 1832 with the passage of another tariff bill that failed to correct of the injustices of the 1828 Tariff of Abominations and to give some relief to the South. Northern beneficiaries of high tariffs succeeded in sustaining tariff rates that did not diminish their profit margins, but gave negligible net relief to the South.

The passage of the 1832 Tariff was viewed by Calhoun, South Carolina, and the cotton-producing Southern states as an unequivocal message that Southern suffering and Southern rights were of no concern to most Northern political leaders. Protectionist tariffs were political bargains in which powerful political and commercial interests united to enrich themselves at the expense of less powerful regions and commercial interests. Given no relief, the growth of Northern population and political power would mean that outrageous tax burdens would be continually laid upon the South to enrich the North. On November 24, 1832, the South Carolina Legislature called a Nullification Convention that nullified the 1828 and 1832 Tariffs as unconstitutional. President Andrew Jackson, although himself a Southerner, threatened armed force to enforce the tariffs. South Carolina raised 27,000 troops to defend against Federal intrusion. With only a few days before military confrontation between Federal troops and South Carolina militias, Congress worked franticly for compromise

The Compromise Tariff of 1833 was negotiated by now Senator Calhoun and Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky and authorized tariff rates to be rolled back gradually to 1816 levels by 1842. This happened just as authorized, and the South prospered under low tariffs. That prosperity, however, came under extreme threat with the Morrill Tariff introduced in 1858, passed by the House in 1860, and by the Senate just days before Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration. The first phase of the Morrill Tariff would raise tariff rates by about 67 percent to levels almost as high as the 1828 Tariff of Abominations. High tariffs were a main campaign theme of the Republican Party in 1860, and Lincoln had campaigned to that effect. He strongly endorsed enforcement of the Morrill Tariff in his inauguration speech on March 4, 1860.

Within weeks, the nation was divided in a clash of arms that would cost more than 750,000 lives. There were long-standing issues over containing slavery in the South, but the Morrill Tariff was a strong provocation for Southern Secession, and Lincoln’s call for troops to enforce the tariff resulted in more secessions and armed conflict.

Union troops did not invade the South to free slaves, and few Union officers or soldiers were fighting to free slaves. In a review of almost one thousand letters and diaries written by Confederate and Union soldiers, James M. McPherson (For Cause and Comrades) found few Confederate mentions about defending slavery or Union mentions about freeing slaves. Indeed, less than 30 percent of Confederate soldiers came from slave-holding families (Philip Leigh). In March 1865, Lincoln’s chief economist, Henry Carey, wrote in a letter to House Speaker Schuyler Colfax stating the present war was about “British Free Trade” [versus U.S. Federal protective tariffs]. Most British leaders believed the American Civil War was essentially over tariffs. Beloved British author, anti-slavery Charles Dickens, wrote in a London periodical: “The Northern onslaught upon slavery is no more than a piece of specious humbug designed to conceal its desire for economic control of the Southern states.” The American Civil War was far less about slavery than this present generation has been led to believe. Yet the end of slavery was one of the consequences of the War.

John C. Calhoun is little remembered today by the general public outside of his home state of South Carolina and is often denigrated in politically correct academic circles. He was a slave owner and is identified with the political doctrines of Nullification, States Rights, and the right of Secession—all doctrines that PC liberals have been taught to hate. But he was one of the giant intellects of political theory in his time, and to the more knowledgeable political historians and political theorists today, he is still a giant, recognized not only in the United States but throughout the entire free world.

It was Thomas Jefferson who first spoke of the doctrine of Nullification in American politics. It was also Jefferson who was the strongest advocate of States Rights in the early days of the American republic. Both concepts are solidly grounded in the Magna Carta of 1215. But it was Calhoun who fully developed both doctrines in the 1830’s and was very successful in using the doctrine of Nullification to negotiate a critical relief for South Carolina and other Southern states from oppressive tariffs that were benefiting the North but devastating the South.

Calhoun also developed an important doctrine called “the concurrent majority.” This differs from a simple numerical majority in that it must constitute a majority of all the major divisions of a political polity. Today this might be called a form of consensus government that takes into account the special needs and rights of major political or regional minorities. Switzerland’s long life as a multi-ethnic republic is usually attributed to the concurrent majority concepts incorporated into its constitution. The concept of the concurrent majority has uses that go beyond politics. It is also a very useful concept for business, social, and community leadership.

Calhoun served the U.S. as Vice President, Secretary of State, Secretary of War, and U.S. Senator and U.S. House member from South Carolina.

In addition to his political genius, Calhoun was amazingly advanced in his analysis and understanding of economic theory. Consequently, many foreign leaders and political scholars visit South Carolina to study Calhoun’s thinking and political theories.

To the extent that Calhoun is denigrated by modern academics and politicians in America, we can be sure that liberty is threatened. The doctrine of States Rights is particularly crucial to constitutional government in the United States. Without States Rights the protection of our liberties from centralized despotism is greatly weakened.