American Economic Struggles 1789 to 2019 - Part 1 of 2

Tariffs are a tax on specified imported goods to provide revenue for the Federal government. In the early history of Federal taxation in the United States, 95 to 100 percent of Federal tax revenues came from tariffs on imported goods. High tariffs on some imported goods have frequently been used to protect U.S manufacturers from competition from lower priced foreign goods. In addition, it has been in the national interest to assure that we do not become dependent on foreign sources for materials and goods critical to national security.

Though sometimes necessary for national security and to correct unfair and dishonest trade practices of rival nations, protectionist tariffs do not have an overall favorable history. Domestically, protective tariffs benefit some commercial or regional interests but seriously damage others. Consumer costs increase and exporters are generally hurt by both domestic cost increases and competitive pressures. Tariffs are essentially a redistribution of wealth through political means and can damage or limit the overall economy. Protected economic interests often become non-innovative drags on the economy and taxpayers.

The Tariff of 1789, signed by George Washington on July 4, 1789, was primarily a revenue tariff that provided some protection for emerging manufacturing industries. Tariffs supported 100 percent of Federal expenditures by 1792. Between 1789 and 1815 tariffs were raised or lowered as funding needs changed, but the average of all tariff rates, including both duty-free imports and dutiable imports, ranged from 6 and 15 percent.

The War of 1812 (1812-1815) started a drift toward higher tariffs—especially protective tariffs shielding U.S. manufactured goods from foreign competition. The British blockade of American ports from 1812 to1815 forced Americans to do their own manufacturing. This began with home manufacturing and became profitable. Most were in New England, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. The Southern economy remained agriculturally based. By the end of the war, 20 percent of the Northern workforce was engaged in manufacturing, compared to only 8 percent for the South.

This was the beginning of two sectional interests: one manufacturing and the other agriculture. At the end of the war, the resumption of a flood of lower-priced British manufactured inventory threatened the continued existence of the North’s budding manufacturing economy.

The Tariff of 1816 sought to pay for the war of 1812 and protect America’s emerging manufacturing industry from European, especially British, competition. A tariff averaging 25 percent was placed on dutiable goods—manufactured cotton and woolen imports. The average tariff on all (dutiable and duty-free) imports increased from about 6 percent to 20 percent by 1820.

However, many prominent Southerners and New Englanders felt that they would benefit enough from the nation’s overall growth from increased industrialization to compensate for their immediate disadvantage. Even James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and John C. Calhoun approved of the compromise. This compromise however, bore the seeds of Northern addiction to protectionist tariffs. Northern manufacturing profits increased by about 25 percent.

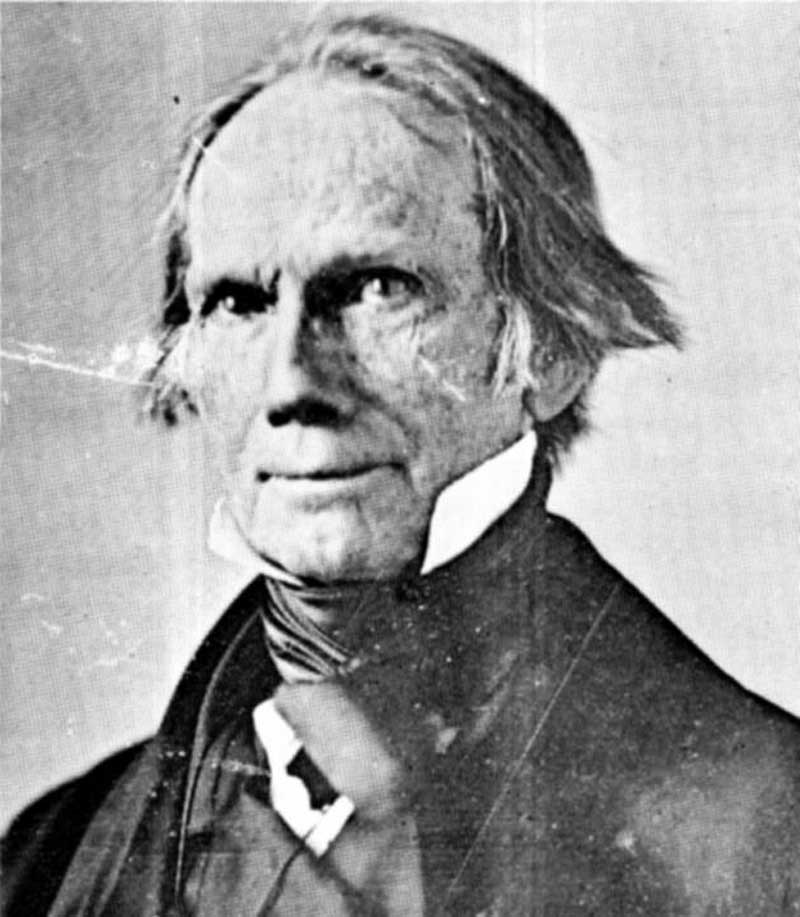

Henry Clay’s clearly protectionist 1824 Tariff had increased average dutiable rates from about 25 percent to 35 percent. Southern protest was so strong that the state legislatures of five Southern states passed resolutions declaring it unconstitutional, and the South Carolina Legislature added that Henry Clay’s “American System” of tariffs and corporate subsidies was “a system of robbery and plunder” that “made one section tributary to another.” The 1824 Tariff resulted in painful increases in the cost of living and doing business in Southern states and severely reduced Southern export business. South Carolina’s export business dropped 25 percent over the next two years. Yet the tragic suffering imposed on the South by the 1824 Tariff was ignored by the Northern special interests that dominated Congress. Higher tariffs meant bigger profits to them.

In 1828, another tariff bill was passed, which was so overbearing and unjust that it is known in history as the Tariff of Abominations. The average dutiable rate was raised to approximately 50 percent and the overall average rate to about 35 percent, the highest in history to that point. The original impetus was that Northern textile manufacturers believed they needed greater protection, but the bill became a comprehensive bribery scheme to win the votes of Middle and Western states for the party of John Quincy Adams in the 1828 election,

In 1832, another tariff bill was introduced, supposedly to correct some of the injustices of the 1828 Tariff of Abominations and to give some relief to the South. The 1828 Tariff had also produced a surplus of government income that many wanted to correct. However, the Northern beneficiaries of high tariffs succeeded in a bill that did not diminish their profit margins. The average overall tariff rate was about 33 percent. The net relief to the South was negligible.

The Last Straw. Passage of the 1832 Tariff was viewed by Calhoun, South Carolina, and the cotton-producing Southern states as an unequivocal message that Southern suffering and Southern rights were of no concern to most Northern political leaders. Protectionist tariffs were political bargains in which powerful political and commercial interests united to enrich themselves at the expense of less powerful regions and commercial interests. Given no relief, the growth of Northern population and political power would mean that outrageous tax burdens would be continually laid upon the South to enrich the North. In November 1832, the South Carolina Legislature called a Nullification Convention that nullified the 1828 and 1832 Tariffs as unconstitutional. President Andrew Jackson, although himself a Southerner, threatened armed force to enforce the tariffs. South Carolina raised 27,000 troops to defend against Federal intrusion. With only a few days before military confrontation between Federal troops and South Carolina militias, Congress worked franticly for compromise

The Compromise Tariff of 1833 authorized tariff rates to be rolled back gradually to 1816 levels by 1842. This happened just as authorized.

Whig Party leaders in congress were again able to pass protectionist legislation in the Tariff of 1842, also known as the Black Tariff. This tariff primarily benefited the iron industry, nearly doubling the rates for both raw and manufactured iron goods. It also raised the percentage of dutiable items from about 50 percent to over 85 percent of all imported items. By 1843, imports had dropped by half, thus actually reducing total tariff revenues. Exports dropped approximately 20 percent.

After the Whigs lost the presidency and Congress in the 1844 election, The Black Tariff of 1842 was replaced by the 1846 Walker Tariff that lowered tariff rates to pre-1842 levels.

The 1857 “Free-Trade” Tariff was passed by a nonpartisan coalition dominated by conservative Southern Democrats and reduced tariff rates to almost free-trade levels. This was strongly opposed by Northern industry and Northern industrial workers.

When a financial panic caused by loose banking practices resulted in a Northern recession in 1857, the Republicans blamed it on free trade and the 1857 Tariff Law. By 1858, the Republicans had submitted new tariff legislation, the Morrill Tariff, to the House Ways and Means Committee. This was supported by Lincoln in the 1860 election. According to Thaddeus Stevens, Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee and a sponsor of the bill, of the two most important issues in the presidential election—excluding slavery from Federal territories and new states and raising Federal import taxes—raising Federal import taxes was the most important.

The Morrill Tariff was signed into law on March 2, 1861, and endorsed in Lincoln’s inauguration speech two days later. It raised the average dutiable tariff from about 20 percent to over 36 percent by 1862, an astonishing 67 percent increase. The overall average including both dutiable and duty-free goods increased from 16 percent to 26 percent. The dutiable rate was scheduled to rise to 47 percent by 1865, more than doubling overall tariff rates. Southern states were already paying 83 percent of the tariff, which was 95 percent of total Federal revenue.

South Carolina and six other cotton producing Southern states began democratic procedures to secede from the United States.

The War and Reconstruction had a devastating effect on the Southern economy. Because of the need for war revenue, the overall U.S. Federal average tariff had been raised to 36 percent by 1865. The average rate was increased during Reconstruction and was over 44 percent by 1870. Thereafter, the overall tariff rate ranged from 27 to 36 percent until Woodrow Wilson’s election to the presidency in 1912. From 1874 to 1904, the Southern economy, hampered by discriminatory protective tariffs and the punitive economic policies of Reconstruction, had a real annual growth rate of only 1.1 percent, barely half the Northern rate of 2.0 percent. The per capita income of white Southerners dropped 36 percent from 1857 to 1879.

Near the beginning of the Great Depression, the highest tariff bill in U.S. history, the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, was passed on June 17, 1930 by Congress. Its purpose was to protect suffering American workers, farmers, and businesses from foreign competition.

~To be continued.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.