Part 5 of a series on Confederate Cavalry

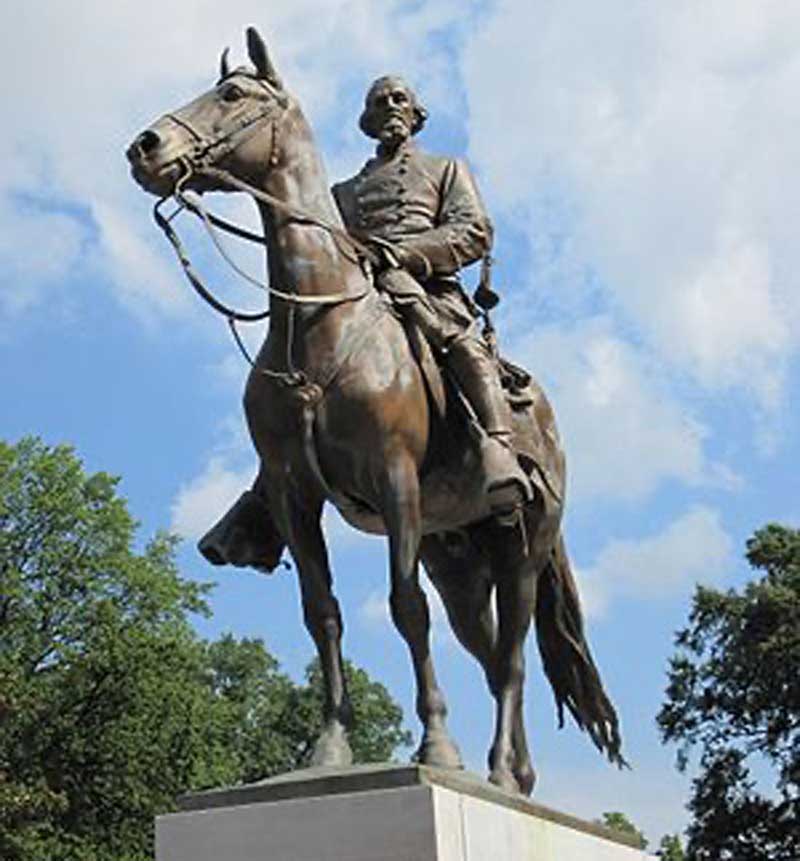

In 2017, Memphis politicians managed to remove the statue of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest from a prominent city park. In the near future, they even plan to move the graves of Bedford Forrest and his wife, Mary Ann. Will removing the memory of Forrest promote social peace or justice in Memphis or in Tennessee? They many not recognize it yet, but they are moving in the wrong direction for truth, social peace, and justice.

Nathan Bedford Forrest was born to William and Miriam Beck Forrest in Bedford County, Tennessee in 1821. He and his twin sister were the first of their parents’ 10 children. The family moved to Hernando, Mississippi in 1834, where William was a blacksmith and farmer. He died in 1837, leaving Forrest, the primary caretaker and defender of the family, at age 16. His mother, Miriam, was a devout Presbyterian and probably had him baptized as an infant, but Bedford did not lean fully that way until later in life. Bedford believed in God, and he respected Christians and the moral teachings of his mother, but he thought Christianity “was a fine religion for women.” He intended to be a worldly success. By an unusual providence of God, however, he married a very strong Christian woman, Mary Ann Montgomery, whose prayers, conduct, and gentle influence with the help of some pastors and Christian officers, finally brought him to publicly embrace Christ as his Lord and Savior in the fall of 1875. Forrest had long before promised God that he would never take a second drink of alcohol, and he never used tobacco in any form, but cursing, gambling, and a fiery temper characterized him until after the war. He did not have much formal education, but he was a gifted entrepreneur, and by 1861 he had become one of the richest men in America. His fortune was made in real estate, cattle-trading, and slave-trading.

However, Forrest had always shown a compassionate and kind side. He showed great respect for women and would not curse around them or allow any other man to curse or behave disrespectfully around them. Women found him invariably courteous and protective, willing to go to great length to relieve them from distress, danger, or insult. He always spoke kindly to children. He did not tolerate adultery or trifling with women among his officers. He was also normally gracious and friendly to men and well liked and respected. He had been elected an Alderman twice while a businessman in Memphis. But many were aware of his fiery intolerance for bad manners, unfairness, unmanly behavior or moral laxity.

Slave-trading had an unsavory reputation, even among slave holders, and especially among Christians, but Forrest was well liked by the slaves he held and those he traded. He never beat slaves. He believed harsh treatment of slaves was unmanly and a foolish lack of business sense. He never broke up families in purchase or sale. Forrest brought over 40 slaves into his original cavalry regiment and freed them before the war ended. Several served in his elite escort company. All but one of over 40 remained loyal to him after the war.

At Fort Donelson, in early 1862, when he was still just a Lt. Colonel, Forrest’s second in command was Major D.C. Kelly, a former Methodist minister, who often acted as chaplain. When six Union gunboats came into sight on the Cumberland River, he called to Kelly, “For God’s sake Parson, Pray! Only God Almighty could save that Fort now.” Forrest strongly encouraged his troops to attend religious services by chaplains and others during the war, and Forrest, whose leadership style was usually to lead from the front, usually attended with them.

Forrest’s personal courage in battle was legendary. He had 30 horses shot from under him of which 29 died. He received four bullet wounds and numerous other injuries. He is said to have killed over 30 men in combat, some in hand-to-hand fighting, and in one case outnumbered four to one. Union General Sherman, who became a friend to Forrest after the war, called him “that devil Forrest” and ordered that he be specifically tracked down and killed no matter the cost. Forrest’s survival through four years of such danger and combat was miraculous. Forrest was also an extraordinary recruiter and motivator of men. Thousands flocked to “Ride with Forrest”

Forrest’s military reputation was damaged by the disproportional fatalities suffered by U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) units at Fort Pillow in 1864, which was then inflamed by Union propaganda. The truth of that battle is contained in last week’s article, part 4 of this series on Confederate Cavalry. He has also suffered from having served as leader of the Ku Klux Klan from 1867 to 1869. But the Klan was fighting against the tyranny of Radical Republican Governor William G. Brownlow in Tennessee. In October 1969, when Brownlow was replaced by moderate Republican, Dewitt Senter, he issued this order:

“Whereas, the Order of the KKK is in some localities being perverted from its original and honorable and patriotic purposes [regulative defense against numerous Reconstruction tyrannies]…and is becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace and public safety for which it was intended….it is therefore ordered and decreed that the masks and consumes of the Order be entirely abolished and destroyed.”

He went on to disclaim those who had used the Klan for personal vengeance and specifically prohibited whipping of blacks or whites or interfering with any man on account of his political opinions. See my April 16, 2020, article “Congress Investigates the Klan 1870 -1871” for more information.

At the end of the war, Forrest was broke. He became president of the Memphis and Little Rock Railroad, but that failed, and he went back to farming and began rethinking his life. About the first week in November 1875, he ran into an old Army friend visiting Memphis. He was surprised and very interested that Raleigh White, perhaps the youngest of his former regimental commanders, had become a Christian and was now a Baptist pastor in Texas. He asked White to pray for him, and they went into a bank lobby and prayed.

On Sunday, November 14, 1875, Forrest, who had been attending church services regularly at the Court Avenue Cumberland Presbyterian Church in Memphis with his wife, Mary Ann, was especially moved. The pastor, George Tucker Stainback (1829-1902), had been a chaplain in the Confederate Army throughout the war. He was congenial, scholarly, and eloquent. His sermon was on Mathew 7: 24-27:

“Everyone who hears these words of mine and does them will be like a wise man who built his house on the rock. And the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat on that house, but it did not fall, because it had been founded on the rock. And everyone who hears these words of mine and does not do them will be like the foolish man who builds his house on the sand, and the rain fell, and the floods came, and the winds blew and beat against that house, and it fell, and great was the fall of it.”

Following the sermon, Forrest found the opportunity to talk with him for a few minutes, telling him, with tears in his eyes, “Sir, your sermon has removed the last prop from under me. I am the fool that built on the sand: I am a poor miserable sinner.”

Dr. Stainback told him he would talk to him more the next evening and that Forrest should read Psalm 51:1-3:

“Have mercy on me, O God, according to your steadfast love; according to your abundant mercy blot out my transgressions. Wash me thoroughly from my iniquity, and cleanse me from my sin! For I know my transgressions, and my sin is ever before me.”

The next evening they met and prayed together. Forrest said that he had put his trust in his Redeemer, and that his heart was finally at peace. The next Sunday morning, Forrest made a public profession of faith and joined the church. Men had begun to see a change in him, but now they saw it more dramatically.

Not long after that, Forrest was invited to speak to a black civil rights group called the “Pole-Bearers” Association. Some whites were uncomfortable with this and were openly critical, but Forrest addressed the black people in love saying;

“I came here with the jeers of some white people, who think that I am doing wrong. I believe I can exert some influence, and do much to assist the people in strengthening fraternal relations, and shall do all in my power to elevate every man, to depress none. I want to elevate you to take positions in law offices, in stores, on farms, and wherever you are capable of going. I came to meet you as friends, and welcome you to the white people. I want you to come nearer to us. When I can serve you I will do so. We have but one flag, one country; let us stand together. We may differ in color, but not in sentiment. Many things have been said about me which are wrong, and which white and black persons here, who stood by me through the war, can contradict. Go to work, be industrious, live honestly and act truly, and when you are oppressed I'll come to your relief. I thank you, ladies and gentlemen, for this opportunity you have afforded me to be with you, and to assure you that I am with you in heart and in hand.”

At the end of his speech a young, black girl presented General Forrest with a bouquet of flowers as a sign of reconciliation between the two races. Forrest accepted the flowers, then leaned down and gently kissed the girl on the cheek. This gesture of reconciliation raised some eyebrows, but Bedford Forrest was a new man with a new heart and did not rage against his critics. His fiery temper was replaced with understanding and humility.

Nearly two years later on his deathbed at the age of 56, on October 29, 1877, he told his pastor, Dr. Stainback, that he was “in peace and not a cloud separated him from his beloved Heavenly Father”

More than 20,000 people attended his funeral in Memphis, of which at least 3,000 were black.

There was a British former slave-trader that also found salvation and wrote what is America’s favorite hymn in 1772. It was John Newton, who wrote Amazing Grace.

It is disheartening to see how much modern political engineering has distorted historical perspective, exaggerated sensitivities, and inflamed vindictive passions. It seems unwise and shameful that so many people are trying to erase every memory of a man whose religious transformation made him reach out to them in love.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.