As I recall, April 12, 1945 was a mild and sunny day in the west side suburb of Cleveland, Ohio where I lived in those long-gone days. World War 11 (that’s “2” for those of you who are Roman numeral “impaired”) was still raging across the Pacific region of the world, even while it appeared to have almost ended in Europe. I was a typical almost nine-year-old in those wonderful times, outside most of the day (except during the coldest days of winter), playing baseball almost every day during the summer, riding my bike, and interacting with my neighborhood “gang” of six or eight preteen guys just like me. If you’ve ever seen that great film, “A Christmas Story”, you’ll know exactly how much of my childhood was spent. Exactly! The author of that book could have been a member of my “gang”. (And yes, I DID drink “Ovaltine”, I DID listen to ‘Little Orphan Annie” on the radio, and I DID have one of her “decoder rings”.)

We only had one ‘rotary’ land line phone, we had no cell phones, no tablets, no computers, no TV’s, no internet, no social media (thankfully) to rot our minds, just glorious days of interacting with other young guys (no girls of course because they were “yucky”) face to face, braggadocio to braggadocio, sharing 5 cent bottles of Coke around the local service station’s Coke machine, 5 cent “fried pies” bought directly from the bakery truck that came around our neighborhood twice each week, “snitching” chips of ice from the back of the “ice man’s” truck, as he delivered big blocks of ice to our neighbors who STILL had “ice boxes” rather than the “newfangled” electric refrigerators, enjoying chocolate phosphates (soda water with chocolate syrup mixed in it), chocolate sodas, and yummy chocolate sundaes (real guys only ate or drank “chocolate stuff”, and it was “expensive”-- .25 cents for a large two-scoop soda or sundae or .10 cents for a big chocolate phosphate) at the corner pharmacy/soda fountain, and listening to our radio “adventure stories” each night WITH our parents. It was a glorious time to be a kid, and if you didn’t experience it I’m sorry for you, because you’ll never know what a wonderful life you missed—you’ll never know the real, safe mental and physical freedom we enjoyed.

All summer, on our bikes, we explored the extensive Metropolitan Park system that encompassed Cleveland like a green necklace, and when we weren’t in “the woods” or searching for “crawdads” in Rocky River, or skipping nice flat stones over its surface to see who could coax the most “skips” from his stone, we were swimming in the reasonably unpolluted Lake Erie, walking on its frozen surface during the winter (unbeknownst to our parents, of course), and as soon as I turned 12, renting a 14 foot boat complete with a 5 h.p. motor and a 2 gallon can of gas, wherein I and one or two of my buddies would spend most of the day out on Lake Erie, even when the waves were “challenging”. The proprietor of “Captain Eddie’s Marina” charged us $12.00 for the boat, motor, and gas for the whole day, with no insurance required, only well-worn cushion life preservers furnished, and no questions asked. Those were great childhood experiences that I’ll remember always. My mother, and most of my friends’ moms, prepared great breakfasts for their offspring (we rarely ate lunch) and told us “be sure you’re home for supper”—which was around 5:00 p.m. every day. We were, without fail, and we always stayed at home, with our parents, from suppertime until the next morning.

But something traumatic happened on the afternoon of April 12, 1945. I was sitting on the steps of the front porch of our large “town house” (3 bedrooms, 1½ baths, kitchen, dining room, large living room, full basement—for which my parents paid about $50.00 to $60.00 per month and considered that “exorbitant”). On that April day, two of my buddies came up to me and greeted me with words that changed the lives of virtually all Americans of those wartime days: “Did you hear that President Roosevelt died today?”, asked one of my buds. My initial response was incredulity, because we all knew that President Roosevelt was as old as the hills (he was 66) and had been president of the U.S. for ALL of our lives, and probably would continue on as president forever (he would like to have done so, of course). I told my bud that he was “full of it” (or some similar words), but he persisted in assuring me that our president had died, and as soon as I went in and asked my mother, I discovered that it was true—she had heard on the radio that Franklin D. Roosevelt had died that day.

I can’t recall whether my parents were sad over the news, or not. As far as I know, during my growing up years my parents never voted (their excuse was that they didn’t want to be called up for ‘jury duty’). My father despised all religions and all politicians and both political parties, but whether or not he was saddened over Roosevelt’s death, I never knew. He never discussed that, or much of anything else, with me. They never discussed the war with me, and all I learned about that terrible conflict I learned by looking at the pictures in Life Magazine every week from 1941 to 1944, and after that I became proficient at reading, and read the war stories in that magazine, and in Look Magazine, both of which my mother brought home every Friday afternoon.

Quoting from History.com (published Nov. 16, 2009) describing that day’s events: “On a clear spring day at his Warm Springs, Georgia retreat, Roosevelt sat in the living room with Lucy Mercer (with whom he had resumed an extramarital affair (an ‘affair’ that had gone on for many years prior and had supposedly been ended-WHL), with two cousins and his dog Fala, while the artist Elizabeth Shoumatoff painted his portrait. According to presidential biographer Doris Kearns Goodwin, it was about 1 p.m. that the president suddenly complained of a terrific pain in the back of his head and collapsed unconscious. One of the women summoned a doctor, who immediately recognized the symptoms of a massive cerebral hemorrhage and gave the president a shot of adrenaline into the heart in a vain attempt to revive him. Lucy Mercer and Shoumatoff quickly left the house, expecting FDR’s family to arrive as soon as word got out….”

The shock and grief experienced by many of the American people were immediate and traumatizing, for FDR was a “hero” to many of them and was greatly loved even by many who had probably never voted for him over his incredible 4 election victories. No one was more shocked than Vice President Harry Truman, who soon was sworn in as President, but who had been kept totally in the dark about “The Manhattan Project”, the U.S. government’s efforts to develop and use an atomic bomb (or two) against our Japanese enemies. Truman learned about this super destructive weapon and made the difficult decision to use these bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, 1945, which soon ended WW11.

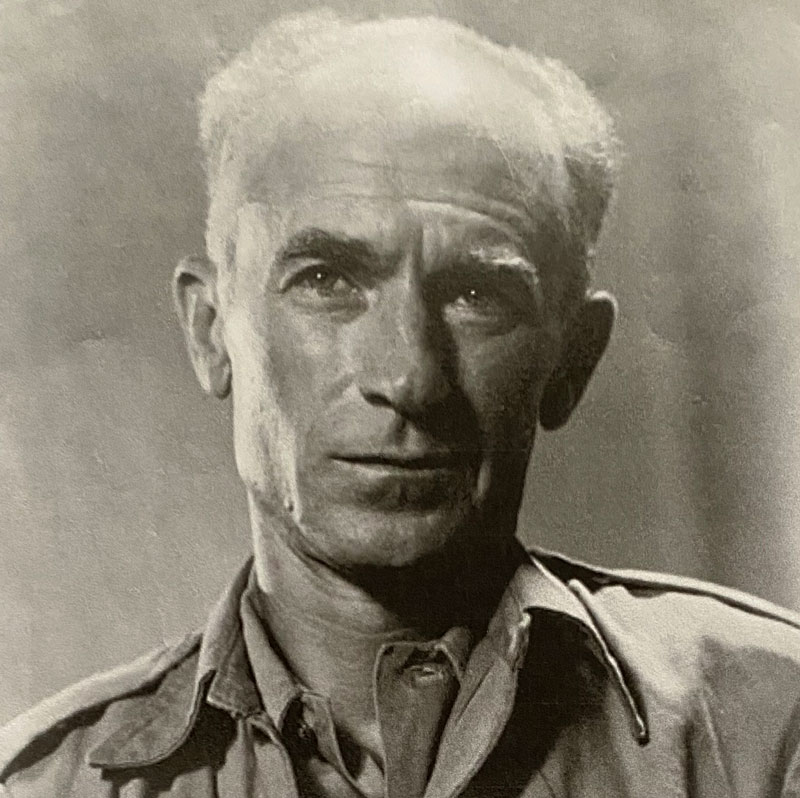

But there was a special man who lived before and during these turbulent years—a man of whom most present-day Americans have never heard --a dedicated war correspondent for Scripps-Howard newspapers who wrote of the warriors of that terrible war from 1940, starting with the Battle of Britain in London, and with a few interruptions, until his death by enemy gun fire on a small island called Ie Shima, near Okinawa, in April, 1945. His name was Ernest Taylor Pyle (1900-1945), but millions of Americans and almost every military person in the U.S. Armed Forces called him “Ernie” Pyle, and his death on April 18, 1945 (six days after President Roosevelt’s death) shocked the American nation almost as much as the death of their long-time president, because virtually all Americans read Ernie’s syndicated columns, many of which were written with his portable typewriter right out on the battlefield and in dangerous areas with his countrymen who were carrying the war to our enemies. Ernie’s style was “folksy”, and he concentrated on telling “human interest” stories from the common soldier’s perspective, in the European Theater from 1942-1944, and in the Pacific Theater in early 1945. President Truman paid sincere tribute to Pyle after his death, saying: “No man in this war has so well told the story of the American fighting man as American fighting men wanted it told. He deserves the gratitude of all his countrymen”. Ernie Pyle truly was “one of a kind”.

Ernie was born on Aug. 3, 1900 to barely educated tenant farmers in Indiana. Ernie despised farming and chose to live an “adventurous” life. He joined the U.S. Naval Reserve during WW1, but that war ended before he could complete his naval training at Great Lakes Naval Training Station. He enrolled in Indiana University in 1919 with plans to become a journalist, but since IU didn’t offer a journalism degree he

majored in economics and took all the available journalism courses that IU offered. Ernie was destined to never complete his studies at IU. During his junior year in 1922, Pyle and three of his fraternity brothers dropped out of school for a semester to follow the IU baseball team on its trip to Japan. The four of them took jobs aboard a freighter, the S.S. Keystone State, and it took them across the Pacific Ocean to intriguing ports like Shanghai, Hong Kong, Manila, and ports in Japan before they made the return trip to the U.S. Ernie’s fascination with traveling around the world continued during his later career as a reporter, which began when he returned to IU, being named editor-in-chief of the Indiana Summer Student, the summer edition of the campus newspaper.

During his final (senior) year at IU he joined the journalism fraternity, Sigma Delta Chi. But it seemed that university life was not for Pyle, for he left IU with only one semester remaining, and never graduated. Ernie was hired as a reporter for the LaPorte Herold newspaper in LaPorte, Indiana, and was paid the princely salary of $25 per week, not a bad sum for 1923. But he worked for the Herold for only three months, then moved to Washington, D.C. to begin working as a reporter for The Washington Daily News, a new Scripps-Howard tabloid style newspaper, and was soon promoted to copy editor as well as still serving as a reporter. He got a raise to $30 per week.

WikipediA tells of Ernie’s personal life as follows: “Pyle met his future wife, Geraldine Siebolds (1899-1945), a native of Minnesota, at a Halloween party in Washington, D.C. in 1923. They married in July of 1925. In the early years of their marriage the couple traveled the country together. In Pyle’s newspaper columns describing their trips, he often referred to her as ‘that girl who rides with me.’ In June, 1940 Pyle purchased property about 3 miles from downtown Albuquerque, New Mexico, and had a modest, 1145 square foot home built on the site. The residence served as the couple’s home base in the U.S. for the remainder of their lives” (only about 5 years for both of them).

About Ernie’s career, WikipediA reported: “By 1926 (Ernie and Geraldeine) had quit their jobs. In ten weeks the couple traveled more than 9,000 miles across the U.S. in a Ford Model T roadster. After briefly working in New York City for the ‘Evening World” and the ‘New York Post’, Pyle returned to the ‘Daily News’ in December, 1927 to begin work on one of the country’s first and its best known aviation column, which he wrote for four years. (It) appeared in syndication for the Scripps-Howard newspapers from 1928 to 1932. Although he never became an aircraft pilot, Pyle flew about 100,000 miles as a passenger. As Amelia Earhart later said, ‘Any aviator who didn’t know Pyle was a nobody.’

“Pyle left…the Daily News to write his own national column as a roving reporter of human interest stories for the Scripps-Howard newspaper syndicate. Over the next six years (1935-early 1942) Pyle and his wife, Jerry,…traveled the U.S., Canada, Mexico, as well as Central and South America, writing about the interesting places he saw and people he met. (During this period he went to London to cover the Battle of Britain from December, 1940 to March, 1941)). Pyle’s column, published under the title of the ‘Hoosier Vagabond’ appeared six days a week in Scripps-Howard newspapers. The articles became popular with readers, earning Pyle national notoriety in the years preceding his even bigger fame as a war correspondent during WW11…. Pyle continued his daily travel column until 1942, but by that time he was also writing about American soldiers serving in WW11.”

Pyle had left London in March of 1941 to return to the States to care for his ailing wife, but returned to Great Britain in the summer of 1942, where he took an assignment that would change his life--he took an assignment from Scripps-Howard newspapers to become its war correspondent, and his exploits in describing the war from the common soldier’s point of view became almost legendary. In late 1942 to early 1943 he was with our troops in North Africa and later was a writing witness to the invasion of Italy until late 1943. With 27 other war correspondents he landed on Omaha Beach during the invasion of Normandy on “D-Day”, June 6, 1944, writing detailed human interest stories about the stress and the carnage of the war and its effects upon our fighting men.

During the brutal North African campaign in late 1942 to early 1943, Ernie wrote numerous stories of his experiences with American fighting men, and these “battle field” stories became much sought after reports for the folks back home in the States. Because of his extensive writing, Ernie Pyle befriended large numbers of both enlisted men and officers, including the top leaders of our military, such as Generals Omar Bradley and Dwight Eisenhower. Ernie often wrote that he was particularly fond of the Army infantry “because they are the underdogs.” Ernie lived among the servicemen where they were, and he was given complete freedom to interview anyone he wanted. Due to the stresses he experienced among combat troops, Ernie did interrupt his battlefield reporting briefly in September, 1943 and again in September, 1944 and returned to his home in New Mexico to recuperate from the stress of living and working under combat conditions, and also to care for his ailing wife, Jerry, who suffered from alcoholism (as did Ernie from time to time) and periods of mental illness (probably bipolar disorder). Pyle also suffered from bouts of “depression” periodically.

In each incidence of his return from the battlefield to recuperate from the stress of living under combat conditions, Ernie would “unwind” at his Albuquerque home with his wife. About a month after he witnessed the liberation of Paris in August of 1944, Ernie wrote a column to his readers, and apologized to them that he “had lost track of the point of the war”, and that he had returned to New Mexico because had he stayed even another two weeks under combat conditions he confessed that he would have been hospitalized with what he called “war neurosis” (probably what we call PTSD today).

Pyle reluctantly accepted Scripps-Howard’s assignment to send him to the Pacific Theater of war in January, 1945, and he headed to the Pacific for what would tragically become his final reporting assignment. Pyle wrote about the Navy and Marine forces in the Pacific. His first “at sea” assignment was on the aircraft carrier, U.S.S. Cabot, and in that column he ran afoul of the Navy and many of his fellow correspondents and newspaper folks, because he unwisely stated that the crews on naval ships had an easier life than his beloved Army infantry experienced in Europe. Ernie was accused of downplaying the hazards and difficulties of naval warfare in his columns, and admitted that his true loyalty was to the servicemen who served in Europe. But he kept writing his columns, reporting on the monumental Battle of Okinawa, which turned out to be the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific Theater during WW11.

It seems that Pyle had continual premonitions of his own death in the war, and wrote letters to friends confessing his fears that he might not survive to witness the end of the war. Quoting from WikipediA regarding Pyle’s death: “On April 17, 1945 Pyle came ashore with the U.S. Army’s 305th Infantry Regiment…on Ie Shima, a small island northwest of Okinawa that Allied Forces had already captured but had not yet cleared of enemy soldiers. The following day, after local enemy opposition had supposedly been neutralized, Pyle was traveling by jeep with Lt. Col. Joseph Coolidge…and three additional officers toward Coolidge’s new command post when the vehicle came under fire from a Japanese machine gunner. The men immediately took cover in a nearby ditch. ‘A little later Pyle and I raised up to look around,’ Coolidge reported. ‘Another burst hit the road over our heads…I looked at Ernie and saw he had been hit.’ A machine gun bullet had entered Pyle’s left temple just under his helmet, killing him instantly.”

Pyle was buried there on Ie Shima, next to two other men who had been killed. He was later reburied in Okinawa but in 1949 his remains were moved to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Honolulu, Hawaii. The fighting men who loved him erected a monument at the site of his death, which still stands to this very day. Ernie Pyle was recognized by his peers as the most famous war correspondent of the WW11 era, and will long be remembered for his extensive newspaper columns that described personal and firsthand stories of “ordinary Americans”, in particular the “G.I.’s” who served in Europe during that tragic conflict. My parents surely read many of Pyle’s columns, but they never discussed him or the war with me. I don’t think I ever read any of his published articles, and I only slowly became aware of Ernie Pyle and his fame during my historical readings about WW11. But then his name slowly faded from the American saga, and our younger generations never knew Pyle and his love for our American fighting men.

It was in 2019, during the commemorations of the 75th Anniversary of the Normandy Landings on June 6, 1944 that I heard his name mentioned again. Today Pyle rests among thousands of his beloved American military men and women in Hawaii. In 1983 Ernie Pyle was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart Medal, which was a truly rare honor accorded to a civilian, by the 77th Army Reserve Command. Ernie Pyle was a true JOURNALIST, reporting honestly on the people and events that he experienced. He was never infected by the cowardly affliction known today as “political correctness”. Too bad that we have so few of his “fraternity” around today!

ADDENDUM: I completed writing this article on June 11, 2019 (I write some of my articles long before they are published). The next day, on June 12, I met an elderly gentleman and his wife. He wore a cap that proclaimed him to be a Navy Veteran of WW11. I struck up a conversation with him and discovered that he had served in the U.S. Navy from 1943 to 1946, serving only in the Pacific Theater, and had participated in six amphibious landings on LST’s (Landing Ship Troops), the last one being the assault and invasion of Okinawa that I touched upon in my article. I asked him if he remembered Ernie Pyle, and a smile crossed his wrinkled face. “Of course I remember Ernie Pyle”, he exclaimed. “I read his columns all the time. All my buddies did. Back around 1976 my wife and I visited his grave in Hawaii, and we considered it to be a very special experience.” When I said goodbye to this elderly warrior, I felt a touch of “déjà vu”, because I was face-to-face with a man who had experienced the violence and triumphs of the very battles that Ernie Pyle had written about, who had read the columns of the man who made his life (and the lives of countless other of his fellow warriors) a little more endurable, and who was painting a verbal picture for me of what he had lived through. I thanked him for his service and told him that I had just written an article about Ernie Pyle. He smiled, nodded his head and said just one word before zipping off in his power wheelchair: “Remember”, he said. “I will”, I assured him. And I will—always, because “worthy men”, like Ernie Pyle, should be remembered!