When taxpayers sell their capital assets, like real property or their shares in a company, net earnings on those sales (capital gains) are generally subject to tax, and net losses on those sales (capital losses) can generally be deducted from income when calculating income tax liability.

One major shortcoming of current policy, however, is that when calculating the capital gain from the sale of an asset, the original purchase price (tax basis) is expressed in nominal terms when subtracted from the selling price. Because no inflation adjustment is made to the original purchase price, capital gains taxes are applied to nominal, not real, increases in wealth, meaning taxpayers are taxed on what is typically a combination of real and fictitious income (although the tax code does provide a few accommodations, such as for qualifying sales of owner-occupied homes and properties transferred to an heir). In some cases, this lack of inflation indexing of the tax basis results in taxpayers paying taxes on what appears on paper to be a capital gain but, due to inflation, is, in real terms, a net loss.

The federal tax code acknowledges this shortcoming with a necessary, albeit imperfect, solution. Long-term capital gains, defined as net gains on assets held for more than one year, are taxed under a rate schedule that differs from the one applied to ordinary income, with lower rates than are applied to ordinary income. Specifically, depending on a taxpayer’s overall taxable income, a rate of either 0 percent, 15 percent, or 20 percent applies to all their taxable long-term capital gains.

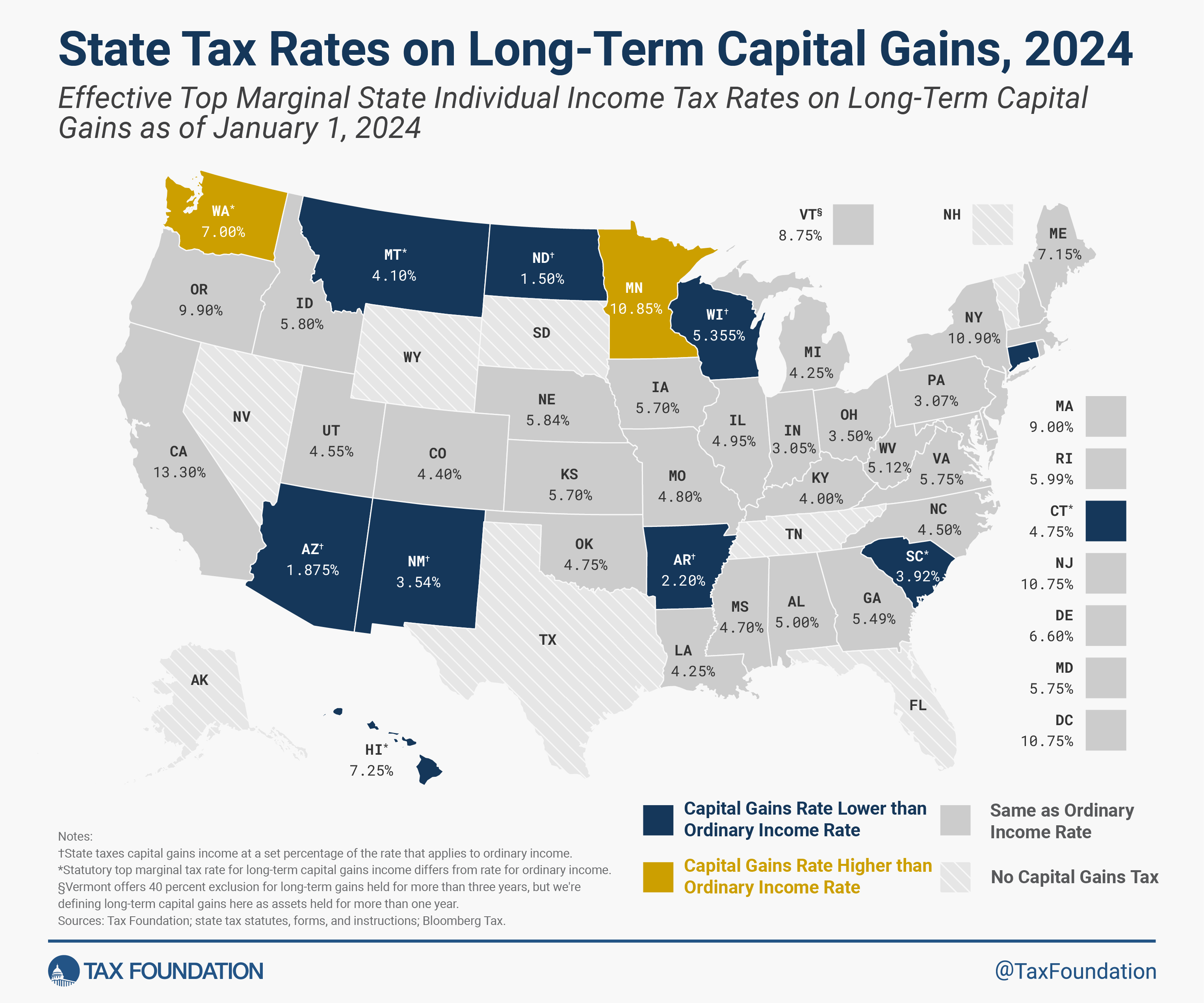

Similar accommodations for the effects of inflation are currently far less common at the state level. Thirty-one states and the District of Columbia overtax capital gains income simply by subjecting capital gains to the same rate schedule that applies to ordinary income. Further, two states—Minnesota and Washington—expose some capital gains to higher rates than apply to ordinary income. Specifically, Minnesota taxes most capital gains at ordinary rates but levies an additional 1 percentage point tax on net investment income exceeding $1 million. Washington imposes a 7 percent tax on capital gains income exceeding $250,000, but the state does not tax ordinary income.

Only nine states, like the federal government, apply lower effective individual income tax rates to long-term gains than to ordinary income, either by applying lower statutory rates or by offering an exclusion for a portion of otherwise taxable capital gains. Meanwhile, seven states avoid this dilemma by forgoing an individual income tax altogether, and New Hampshire, uniquely, currently taxes interest and dividends income but does not tax ordinary income or capital gains income.

Eleven States Tax Capital Gains Income Differently Than Ordinary Income

State Top Marginal Tax Rates on Ordinary Income and Effective Top Marginal Rates on Long-Term Capital Gains Income as of January 1, 2024

| States Taxing Capital Gains at Lower Rates Than Ordinary Income | ||

| State | Top Marginal Rate on Ordinary Income | Effective Top Marginal Rate on Long-Term Capital Gains Income |

| Arizona (a, b) | 2.5% | 1.875% |

| Arkansas (a, c) | 4.4% | 2.2% |

| Connecticut (d, e) | 6.99% | 4.75% |

| Hawaii (d) | 11% | 7.25% |

| Montana (d) | 5.9% | 4.1% |

| New Mexico (a, f) | 5.9% | 3.54% |

| North Dakota (a, g) | 2.5% | 1.5% |

| South Carolina (a, h) | 6.4% | 3.92% |

| Wisconsin (a, i) | 7.65% | 5.355% |

| States Taxing Capital Gains at Higher Rates Than Ordinary Income | ||

| State | Top Marginal Rate on Ordinary Income | Effective Top Marginal Rate on Capital Gains Income |

| Minnesota (j) | 9.85% | 10.85% (e) |

| Washington (d, k) | 0% | 7% (f) |

(b) Arizona excludes 25 percent of net long-term capital gains, with the remainder taxed at ordinary rates.

(c) Arkansas excludes 50 percent of net long-term capital gains, with the remainder taxed at ordinary rates. The amount of a net gain that exceeds $10 million is exempt.

(d) Statutory top marginal tax rate for long-term capital gains income differs from rate for ordinary income.

(e) In Connecticut, capital gains tax liability is limited to 3.4 percent of a taxpayer's total income.

(f) New Mexico currently excludes the greater of $1,000 or 40 percent of a taxpayer's net long-term capital gains. Beginning in 2025, New Mexico will exclude the greater of $2,500 or 40 percent of up to $1 million of a taxpayer's long-term capital gain.

(g) North Dakota offers a 40 percent exclusion.

(h) South Carolina excludes 44 percent of net long-term capital gains.

(i) Wisconsin allows a 30 percent deduction on net long-term capital gains and a 60 percent deduction for farm assets.

(j) Minnesota's 10.85 percent top marginal effective rate on capital gains income includes a 1 percent tax on net investment income exceeding $1 million.

(k) In Washington, a standard deduction of $250,000 (regardless of filling status) is allowed before the 7 percent rate applies. Some types of capital gains income are excluded from taxation.

Sources: Tax Foundation research; state statutes, forms, and instructions; Bloomberg Tax.

At the state level, applying lower rates to long-term capital gains income is a good first step to help compensate for the fact that capital gains taxes apply to nominal, not real, capital gains. As such, more states should consider joining the nine that currently apply lower effective rates to long-term capital gains, either by applying a lower rate to long-term capital gains income or providing an exclusion for a certain percentage of otherwise taxable capital gains. Additionally, states should also ensure they provide robust and timely deductions for capital losses.

It is important to keep in mind, however, that even when lower rate schedules or exclusions are granted, capital gains taxes are nevertheless a form of double taxation. To illustrate this, imagine an individual who decides to save for the future by purchasing stock in a company. Sometimes, those shares are purchased through tax-advantaged investment accounts, like a 401(k) or IRA, ensuring a taxpayer’s invested income is taxed only once, either on the way in (Roth accounts) or on the way out (traditional accounts).

Oftentimes, however, investors purchase stock using ordinary wage or salary income that has already been taxed under the standard federal and state individual income tax rate schedules. Under favorable circumstances, over time, a taxpayer’s initial investment will grow. But most growth is the result of corporate profits that will have already been subject to corporate income taxes by the time they reach the investor in the form of interest or dividends income, so those returns to the investor will be smaller than they would have been in the absence of federal and state corporate income taxes. Years or decades later, when the investor sells their shares and realizes their gains, that income will be taxed again, based on its nominal, rather than real, growth. While applying lower rates to realized capital gains helps offset some of the effects of inflation that occurred between when those capital assets were bought and sold, it does not change the fact that, in most cases, the earnings received by the taxpayer will have already been reduced by the corporate income tax.

At face value, lower rates on long-term capital gains income can look like a form of preferential tax treatment, but when inflation and other layers of taxes are taken into consideration, it is easy to see why that notion is misguided. When evaluating the tax treatment of investment income, state policymakers should consider all layers of taxes on those earnings, including corporate income taxes, and understand how the failure to inflation index the tax basis, combined with most states’ failure to adjust rates accordingly, results in the widespread overtaxation of capital gains income in the United States.

Savings and investment are critical activities, both for individuals’ and families’ financial security and for the health of the national economy as a whole. As such, policymakers should consider how they can help mitigate—rather than add to—tax codes’ biases against saving and investment.

----------------------------

Katherine Loughead is a Senior Policy Analyst & Research Manager with the Center for State Tax Policy at the Tax Foundation, where she serves as a resource to policymakers in their efforts to modernize and improve the structure of their state tax codes.

SOURCE: Click HERE