Media Bias, KGB Funding of Antiwar Groups, and Powder Puff Air-Warfare

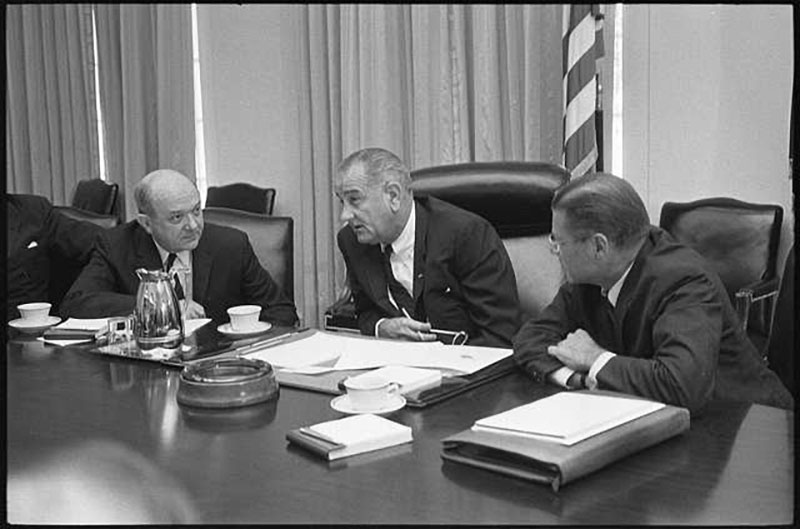

Secretary of State Dean Rusk, Pres. Lyndon Johnson, Defense Sec. Robert McNamara.

The Vietnam War was a Two-Front war in this sense: There was a military front and a political and propaganda front. The military front was Vietnam, but also Laos, and Cambodia. The political and propaganda front was the American home front and an intense battle for American public .opinion.

The leaders of North Vietnam were strong believers in the wisdom of studying history. They remembered that the French did not abandon Indochina after eight years because they lost the Battle of Dien Bien Phu in May 1954, where 14,000 French Union and Foreign Legion troops in an isolated mountain valley were defeated by 80,000 unexpectedly mobile and well-equipped North Vietnamese. The North Vietnamese had put their primary focus on undermining the will of the French people by propaganda and political agitation. Dien Bien Phu was a tragic but recoverable loss, but in a two-front war, it was the propaganda and agitation in France, which was ultimately decisive and had worn out the French Parliament and lost Indochina. Between 1959 and 1963, the Soviet Union began sowing seeds of propaganda and agitation in the U.S. through Communist front organizations and sympathetic academic and media organizations. Hence the media reporting on the war typically reflected a leftist, anti-war bias.

The Soviet Union and the American Left were actively engaged in organizing and funding protests, agitation, and propaganda events from the beginning. We have credible inside testimony of this from the highest ranking Soviet military intelligence officer ever to defect. Colonel Stanislav Lunev had long been disillusioned with Communism and the Soviet style of government, but he defected in 1992, following the breakup of the Soviet Union, when he became further disillusioned with the influence of oligarchic corruption under Russian Federation President Boris Yeltsin. The following quote comes from Col. Lunev’s 1998 book, Through the Eyes of the Enemy:

“The KGB helped to fund just about every antiwar movement and organization in America and abroad, and during the Vietnam War, the Soviet Union gave $1 billion to American antiwar movements, more than it gave the Viet Cong.”

($1 billion during the peak of the Vietnam War would be $5.4 billion in 2023 dollars.)

In 1970, the U.S. House Committee on Internal Security published a report on “Subversive Involvement in the Origin, Leadership of the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam and its Predecessor Organizations” that corroborates some detail of Communist antiwar organization and funding.

A 2005 research paper for Air University by Navy LCDR Marco P. Giorgi and republished as a book in 2012 entitled, Losing the War for U.S. Public Opinion during the Vietnam War, contains a precise summary:

“Realizing they were not likely to win on the field of battle against American forces, the North Vietnamese communists opened up a new front on American soil. The weapons were propaganda and agitation…The anti-war movement undermined public support for the Vietnam War through the mass media, the alternative press, and protests.”

According to Giorgi, the soldiers of the antiwar movement were misguided American citizens fighting a war for a ruthless and brutal Communist ideology.

Under pressure from the New York Times and exploding distorted liberal media coverage over a North Vietnamese contrived false issue of discrimination against Buddhists, President John F. Kennedy’s ill-considered regime change plan, which resulted in the assassination of South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem and his brother, Ngo Dinh Nhu, threw the South Vietnamese Government and Army into chaos for over two years. North Vietnam exploited this confusion by sending 240,000 troops into south Vietnam from 1964 to 1967. U.S. advisory troops numbered only 16,000 at the end of 1963, but this North Vietnamese invasion and President Johnson’s softball strategy for stopping the North Vietnamese invasion led to an enormous force of 536,000 American troops in South Vietnam at the end of 1968.

American Antiwar March with Viet Cong Flags.

Soviet funding of propaganda and agitation increased sharply in 1968. In February 1968, during the week-long Vietnamese Tet Holiday, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Viet Cong (VC) launched a desperate major offensive—desperate because they were losing the war. The North Vietnamese were losing more soldiers than they were able to replace, and more supplies were being destroyed than they could resupply. The Tet offensive, using both infiltration and mass attack, planned to bring down 36 provincial capitals and the Saigon government. However, they were absolutely crushed with such high casualties that North Vietnam considered postponing further war efforts. More than 45,000 of the 85,000 NVA and VC troops employed during Tet were killed in action. NVA and VC killed in action extended to more than 100,000 in the first six months of 1968. The VC were practically eliminated as a major threat.

But American television made it look like the Communists were winning. When North Vietnam realized that anti-war protests and an increasingly anti-war American media had turned a devastating Communist defeat into a resounding political victory, it bolstered their resolve to persevere and pay even more attention to propaganda and agitation on the U.S. home front. While the anti-war movement only had a minor impact on the vast majority of the American public, it had a major impact on the news media and Congress.

There were only 23,000 American advisory troops in Vietnam at the end of 1964. The first ground combat troops were sent to South Vietnam in March 1965. President Johnson and Defense Secretary McNamara adopted a strategy called graduated or gradual escalation that was strongly opposed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and other military leaders. This strategy was conceived by the so-called Whiz Kids from the Rand Corporation, a Defense related think tank, but was contrary to classic military doctrine and lessons learned over several centuries of warfare.

The gradual escalation strategy included limited bombing of North Vietnam called Operation Rolling Thunder. Between March 1965 and October 1968 this involved mostly secondary targets selected during regular Tuesday meetings at the White House with NO military leaders present. Targeting was extremely restrictive. Overall Pacific Commander Admiral Grant Sharp called this “Powder Puff Airpower.” At first, Air Force and Navy pilots were not allowed to strike surface-to-air missile sites (SAMs) unless they fired on them first. Restrictions continued to prohibit destruction of SAM sites under construction and missiles during transport. As a consequence, during subsequent attacks on military targets around Hanoi, we lost over 1,000 pilots and crew-members and about 50% of the F105s ever built, 395 of 833. The bombing was temporarily stopped 16 different times in a costly “powder puff” effort to encourage North Vietnam to seek a negotiated peace—a futile effort that conspicuously failed to recognize that Communists respond only to superior force and do not negotiate in good faith. The bombing halts were merely exploited by North Vietnam as an opportunity to build up strength for continued aggression against South Vietnam.

During the war, we lost 922 aircraft over North Vietnam and another 2,800 fixed-wing aircraft in South Vietnam and Laos. We lost over 5,600 helicopters and over 4,800 helicopter pilots and crew-members.

This failed strategy of gradual escalation was described by Admiral Sharp as,

“…the most asinine way to fight a war ever imagined.”

There were finally Senate hearings on this, and as a result, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was forced to resign by the end of February 1968.

President Richard Nixon took office in January 1969. He introduced a Vietnamization program reducing U.S. troop strength and building up South Vietnamese combat forces. He eventually realized that negotiations with North Vietnam were largely futile and decided on the strategy that had been recommended SIX times, starting in 1965, by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Admiral Sharp, and other military leaders—a strategy that involved intensive strategic bombing of ALL North Vietnamese military, logistical, and transportation targets and mining important North Vietnamese harbors, including many previously off-limit targets in Hanoi and the port of Haiphong.

The first major bombing campaign on April 10, 1972, was called Operation Linebacker 1. This occurred during a major invasion by North Vietnam called the Easter Offensive which only involved the South Vietnamese Army and no U.S. ground troops. (Vietnamization had reduced in-country U.S. military forces to 24,000.) The bombing damage was severe and had more impact on the war making capability of North Vietnam than was achieved during three and one-half years of Operation Rolling Thunder. This forced the North Vietnamese to negotiate by early October 1972. However, Nixon realized in mid-December that North Vietnam was only stalling for time. Operation Linebacker II was launched on December 18. This included 11 days of heavy bombing by 207 B-52 bombers and almost as many other Air Force and Navy combat aircraft. The last bombing mission on December 29, 1972, brought North Vietnam’s leaders to their knees.

On January 27, 1973, Peace Accords were signed in Paris. The terms were not as strong as Nixon and the South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu wished. A media-driven Congress anxious to get out of Vietnam was already undermining Nixon’s negotiating options. The last American troops and POWs left on March 29. In June however, Congress began to default on promised annual financial and weapons support to South Vietnam. The Fiscal Year 1975 support for South Vietnam was reduced by 69 percent, which military analysts considered completely inadequate for South Vietnam’s self-defense.

In early 1975, North Vietnam launched another huge, Soviet-financed Spring Offensive. Cambodia fell on April 16, literally running out of ammunition. Saigon fell on April 30, 1975.

During the next three years after the fall of Saigon, more than 3.5 million civilians in South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia were either murdered, starved to death, or drowned in the South China Sea trying to escape the brutality of the victorious new Communist governments.

This was a staggering tragedy nearing World War II-Holocaust-levels and an ugly chapter of American political history. Not surprisingly, this dreadful carnage of once free peoples has been largely swept clear of public memory by the dominant news media and academic and political establishments.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.

Mike Scruggs is the author of two books: The Un-Civil War: Shattering the Historical Myths; and Lessons from the Vietnam War: Truths the Media Never Told You, and over 600 articles on military history, national security, intelligent design, genealogical genetics, immigration, current political affairs, Islam, and the Middle East.